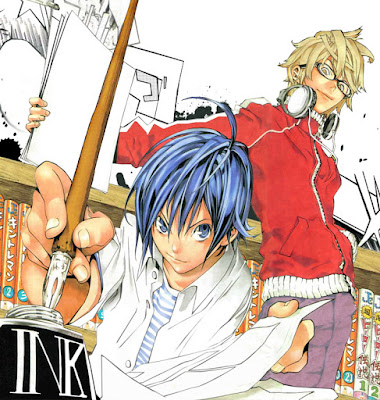

The man who created the smash hit Death Note, Tsugumi Ohba, shifts from the supernatural genre to take on a more realistic approach to Shonen. Ohba writes much closer to home by creating a story about a team of young men who are trying to become Mangaka and, ultimately, have their manga turned into an Anime. The product is both an entertaining look into the workings of the Japanese Manga industry and the attempt to apply the Death Note narrative structure to a seemingly mundane subject.

It’s hard not to compare Bakuman to Death Note, Ohba has a narrative style that commands the attention of the audience and adds suspense with surprising regularity. One could claim that the idea itself is what really kept people interested in Death Note, but now that Ohba has applied that style to the rather mundane story of two kids writing comics and made it just as intense as Death Note, so clearly he has unlocked a structure and pacing that simply works. The impact of cliffhangers is such an important and difficult aspect in serialized content and yet Bakuman is able to create a compelling stopping point nearly every episode with story lines like “will they meet their dead line” or “What will happen when they meet with the manga editor.”

It’s hard not to compare Bakuman to Death Note, Ohba has a narrative style that commands the attention of the audience and adds suspense with surprising regularity. One could claim that the idea itself is what really kept people interested in Death Note, but now that Ohba has applied that style to the rather mundane story of two kids writing comics and made it just as intense as Death Note, so clearly he has unlocked a structure and pacing that simply works. The impact of cliffhangers is such an important and difficult aspect in serialized content and yet Bakuman is able to create a compelling stopping point nearly every episode with story lines like “will they meet their dead line” or “What will happen when they meet with the manga editor.”

Certainly some credit should be given to director Kenichi Kasai for translating those elements so effectively to animation but the perfection of the Shonen style lies with Ohba. Each new challenge that Mashiro and Takagi has the same feeling that Bleach or Dragon Ball would have except instead of an epic fight scene we get scenes of two guys drawing. That is the true beauty of Bakuman; it is an elegant story that takes the audience on a ride through an artist’s life while they try to get a foot in the door at the big manga publishers and it feels as exciting as a Shonen action show. The energy and drive of the main characters are inspiring, one will find it hard not to buy in to the suspense at each turn from the sheer fact that you want to see these characters succeed.

Bakuman’s characters are the vehicle which audience sees the world. An exceptional narrative trick that Bakuman achieves is to present the world through the eyes of the main characters including their own personal misconceptions and bias’. Eiji Niizuma, a genius mangaka who becomes the youngest person ever serialized, is perceived as a rival for most of the series, a hurdle that Mashiro needs to overcome. However, once Mashiro spends a good amount of time with Niizuma he comes to realize that his rival is not superhuman but just another young artist with failings of his own. At that point the concept of the “rival” in Bakuman changes and the artists that Mashiro has met at that point become comrades, able to exchange information and help each other improve. The true rival is the self, honing and refining ones craft is the way one will win in this world and the concept of the prodigy Mangaka is dismissed, at least in the first season.

Bakuman’s characters are the vehicle which audience sees the world. An exceptional narrative trick that Bakuman achieves is to present the world through the eyes of the main characters including their own personal misconceptions and bias’. Eiji Niizuma, a genius mangaka who becomes the youngest person ever serialized, is perceived as a rival for most of the series, a hurdle that Mashiro needs to overcome. However, once Mashiro spends a good amount of time with Niizuma he comes to realize that his rival is not superhuman but just another young artist with failings of his own. At that point the concept of the “rival” in Bakuman changes and the artists that Mashiro has met at that point become comrades, able to exchange information and help each other improve. The true rival is the self, honing and refining ones craft is the way one will win in this world and the concept of the prodigy Mangaka is dismissed, at least in the first season.

The characters also work as an audience stand in, as they learn about the process of creating manga so does the audience. Again, entering the world of Manga publishing feels extremely Shonen but instead of a fantasy world what the audience is getting is a detailed look into the world of manga publishing. I’m glad that Ohba decided to frame the story this way because while manga fans in Japan might know how the big magazines work I find myself learning a ton by watching Mashiro and Tagaki go through the process. The fact that Shonen “Jack” relies on reader’s questionnaires is, for example, a specific detail of Manga publishing that is just second nature to a Japanese manga fan yet I had no idea such a thing existed, and of course didn’t realize that questionnaires can make or break a mangaka. Bakuman treats them with the life or death gravity that any young artist would feel when awaiting rejection.

With so much good in Bakuman it is disappointing to say that what Bakuman does wrong almost distracts from the quality. The romance between Mashiro and Miho is laughably bad, so unrealistically bad. It’s designed to fit into the world of Bakuman where success as a Mangaka should lead to all rewards. One of those rewards is love, and while this does fit into the Shonen structure there is a sense of realism to Bakuman that makes it feel icky at the same time. In Bleach, Ichigo having to become a better fighter to rescue Rukia feels right, but having Mashiro’s success as a Mangaka deliver the girl of his dreams into his arms feels cheap, misogynistic, and crushes the realism of the show. The portrayal of women in the show as a whole is weird, as I’ve written about previously all accusations of misogyny are for good reason. There is a general sense that men have their goals and women are required to support them, because they can’t fully understand men’s dreams. It’s repulsive.

Even with the romance souring a good third of the show there is still a lot to like about Bakuman. The application of the Death Note formula to the mundane story of two upcoming Mangaka is exceptional. Ohba has made his own life, in the eyes of Anime and Manga fans, a roller coaster of disappointment and joy. I’ve also learned more about how the comics publishing industry in Japan works from watching this one show than in ten years of being an Anime fan. Any fan of Japanese animation, especially Shonen, will love Bakuman as long as they can get passed the uglier elements of the narrative.

Even with the romance souring a good third of the show there is still a lot to like about Bakuman. The application of the Death Note formula to the mundane story of two upcoming Mangaka is exceptional. Ohba has made his own life, in the eyes of Anime and Manga fans, a roller coaster of disappointment and joy. I’ve also learned more about how the comics publishing industry in Japan works from watching this one show than in ten years of being an Anime fan. Any fan of Japanese animation, especially Shonen, will love Bakuman as long as they can get passed the uglier elements of the narrative.

Good

- Well placed cliffhangers keep the audience eager to watch

- The audience learns about how Manga publishing in Japan really works.

- Mangaka as Shonen heroes structure is brilliant.

Bad

- Overbearingly negative attitude towards women

- Romance in Bakuman is, at best, childish

Women are portrayed as obstacles in the path of men who are trying to reach their goals. In the most direct sense, Moritaka’s mother refused to allow him access to his Uncle’s studio and refused to accept his dream of becoming a Mangaka. It was his Father and Grandfather who stepped in and insisted that he be allowed to pursue his dream, telling the mother that some things “men have to do that woman can’t understand”. This applies also to romantic relationships and why Miho is set up as the ideal woman. Miho also has a goal she is trying to accomplish, and no other woman in the series seems to share her values. She wants to put off their relationship knowing that it would get in the way of her dream of becoming a voice actress. The “normal” girl is shown during a scene when a young girl chases her boyfriend to the roof chastising him the entire way for changing his High School of choice. She is upset because they won’t be together. This is what Ohba sees as the normal girl, chasing after a boy and having no goals of her own. The action of the young man is what the author acknowledges as the correct choice, personal progress over romance.

Women are portrayed as obstacles in the path of men who are trying to reach their goals. In the most direct sense, Moritaka’s mother refused to allow him access to his Uncle’s studio and refused to accept his dream of becoming a Mangaka. It was his Father and Grandfather who stepped in and insisted that he be allowed to pursue his dream, telling the mother that some things “men have to do that woman can’t understand”. This applies also to romantic relationships and why Miho is set up as the ideal woman. Miho also has a goal she is trying to accomplish, and no other woman in the series seems to share her values. She wants to put off their relationship knowing that it would get in the way of her dream of becoming a voice actress. The “normal” girl is shown during a scene when a young girl chases her boyfriend to the roof chastising him the entire way for changing his High School of choice. She is upset because they won’t be together. This is what Ohba sees as the normal girl, chasing after a boy and having no goals of her own. The action of the young man is what the author acknowledges as the correct choice, personal progress over romance.

Miyoshi’s role in the story says a lot about Ohba’s view towards women. It is comparable to his Death Note character Misa. Misa initially begins her own Death Note fueled rampage in order to get Kira’s attention, but once Kira pretends to be in a relationship with her she becomes completely obedient to him. Akito’s mother also follows this pattern, while she is a successful school teacher her husband losing her job breaks her, almost cripples her emotionally. She decides to channel the disappointment in her husband into her children, pushing them hard so they don’t fail. Instead of picking herself up and focusing on her career, she relied on her husband to create a stable household. It seems that Ohba’s view on women is that they only show initiative to attract men. The obvious way this is portrayed in both Death Note and Bakuman suggests this might be a conscious bit of social criticism; however it is more likely that he just can’t write female characters in any other way. Nothing is known about the Mangaka’s personal life, if he is married or in a relationship, the most the public knows is that he collects teacups and “develops manga plots while holding his knees on a chair.” Whether his opinions on women come from bitterness or ignorance may never be answered definitively but the blankly negative female character he has written makes the answer a bit obvious. There is, of course, one exception to his negative female characters. The heroine of Bakuman, Miho, is written as the ideal woman.

Miyoshi’s role in the story says a lot about Ohba’s view towards women. It is comparable to his Death Note character Misa. Misa initially begins her own Death Note fueled rampage in order to get Kira’s attention, but once Kira pretends to be in a relationship with her she becomes completely obedient to him. Akito’s mother also follows this pattern, while she is a successful school teacher her husband losing her job breaks her, almost cripples her emotionally. She decides to channel the disappointment in her husband into her children, pushing them hard so they don’t fail. Instead of picking herself up and focusing on her career, she relied on her husband to create a stable household. It seems that Ohba’s view on women is that they only show initiative to attract men. The obvious way this is portrayed in both Death Note and Bakuman suggests this might be a conscious bit of social criticism; however it is more likely that he just can’t write female characters in any other way. Nothing is known about the Mangaka’s personal life, if he is married or in a relationship, the most the public knows is that he collects teacups and “develops manga plots while holding his knees on a chair.” Whether his opinions on women come from bitterness or ignorance may never be answered definitively but the blankly negative female character he has written makes the answer a bit obvious. There is, of course, one exception to his negative female characters. The heroine of Bakuman, Miho, is written as the ideal woman.